Last week, British parents who had hidden their child’s gender from the world finally revealed that their five year old, now ready to enter school, is a boy. While the parents had hoped to raise their son Sasha in a gender-neutral way (“Stereotypes seem fundamentally stupid. Why would you want to slot people into boxes?”), their approach raised eyebrows and controversy. Were they creating an environment where their child could find his own gender identity, free from crippling societal expectations, or were they conducting a bizarre and possibly harmful experiment on a family member?

Putting aside the issue of whether the parents acted appropriately, the story raises fascinating questions about gender-specific traits and preferences. To what degree are gender differences innate and biological, and to what extent do they arise out of societal modeling and environment?

Some (including Sasha’s parents) may see gender preferences as being primarily influenced by human social pressures, but there are indications of biological influences as well. For example, girls with a particular genetic condition that exposes them to high prenatal levels of androgen often show “masculine” toy preferences, even when their parents strongly encourage them to play with female-typical toys. Given the intertwining impacts of nature and nurture in human societies, can we learn anything from our animal relatives who grow up free from human societal norms?

In this post, I’d like to take a look at two recent studies that examine differing male and female toy preferences in primates.

Male Monkeys Prefer Trucks

First, in 2009 a research team led by Janice Hassett of the Yerkes National Primate Center at Emory University reported on experiments in which they the researchers to see whether rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) would exhibit gender-specific toy preferences similar to those of human children.

In humans, studies have shown that boys gravitate strongly to stereotypically “masculine” toys such as trucks and other vehicles, while girls are less rigid, spending relatively equal amounts of time playing with boy-favored toys and with more traditionally “feminine” toys such as dolls. One hypothesis put forward to explain this difference has been that boys face greater societal discouragement when they play with “girl toys” than girls do in the reverse situation. The researchers figured that by looking at rhesus monkeys, who don’t face comparable social pressures to conform to gender roles, they might be able to illuminate biological influences on toy selection as well.

Of course I'm not playing; you gave me a Raggedy-Ann. Pass me that truck. Now. (photo credit: J.M.Garg, Wikipedia)

In their study, the researchers compared how 34 rhesus monkeys living in a single troop interacted with human toys categorized as either masculine or feminine. The “masculine” set consisted of wheeled toys preferred by human boys (e.g., a wagon, a truck, a car, and a construction vehicle); the “feminine” set was comprised of plush toys comparable to stuffed animals and dolls (e.g., a Raggedy-Ann™ doll, a koala bear hand puppet, an armadillo, a teddy bear, and a turtle). Individual monkeys were released into an outdoor area containing one wheeled toy and one plush toy, with the researchers taping all interactions using separate cameras for each toy, identifying all specific behaviors, and statistically analyzing the results.

The results closely paralleled those found in human children. As with human boys, male rhesus monkeys clearly preferred wheeled toys over plush toys, interacting significantly more frequently and for long durations with the wheeled toys. Also mirroring human behavior, female rhesus monkeys were less specialized, playing with both plush and wheeled toys and not exhibiting significant preferences for one type over the other. Here’s a chart illustrating the similar gender preferences of humans and rhesus monkeys (the information regarding human preferences comes from a 1992 study by Sheri Berenbaum and Melissa Hines):

The researchers noted that these similarities show that distinct male and female toy preferences can arise in the absence of socialization pressures and hypothesized that “there are hormonally organized preferences for specific activities that shape preference for toys that facilitate these activities.”

Barbie Really Is a Stick Figure

Next, in a brief paper published in 2010, Sonya Kahlenberg of Bates College and Richard Wrangham of Harvard University presented the first evidence of wild male and female primates, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in the Kanyawara chimpanzee community of Kibale National Park, Uganda, interacting differently with play objects.

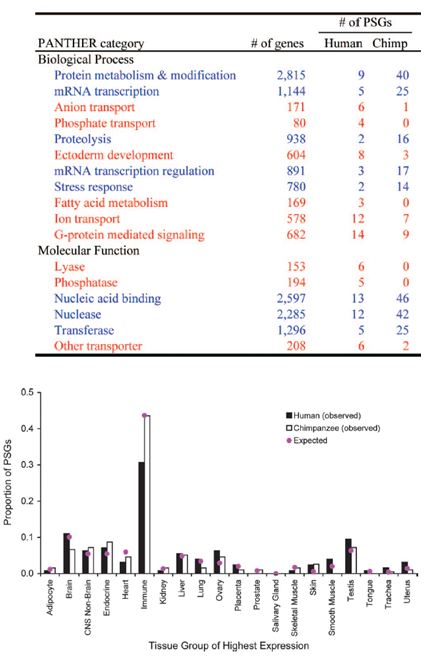

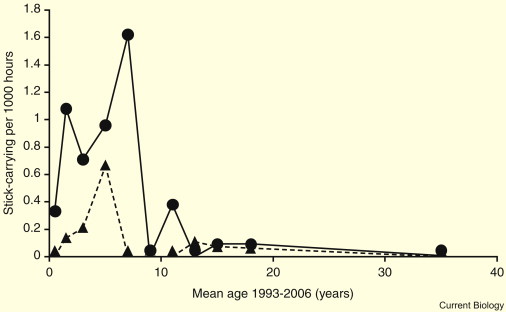

Over a 14 year period, Kahlenberg and Wrangham observed that juvenile Kanyawara chimpanzees tended to carry sticks in a manner suggestive of rudimentary doll play and that the behavior was more common in females than in males. Juvenile chimps, particularly females, would carry around small sticks for hours at time while they engaged in other daily activities such as eating, climbing, sleeping, resting and walking. While the same chimps used sticks as tools for specific purposes, the researchers were unable to discern any practical reason for the stick-carrying. The following chart shows the degree to which female chimps were more likely to engage the in stick carrying behavior:

Age and sex differences in the rate of stick-carrying in chimpanzees. Females: circles, solid line. Males: triangles, dashed line.

The researchers hypothesized that “sex differences in stick-carrying are related to a greater female interest in infant care, with stick-carrying being a form of play-mothering (i.e. carrying sticks like mother chimpanzees carrying infants).” In support of this proposition, they pointed to several factors. First, they never observed stick carrying by any female who had already given birth; that is, stick-carrying ceased with motherhood. Also, the chimps regularly carried sticks into day nests where they “were sometimes seen to play casually with the stick in a manner that evoked maternal play.” Finally, nurturing behavior towards objects like sticks had previously been reported in captive chimps and documented on a couple of occasions in the wild.

Also, the researchers suggested a social rather than biological basis for the behavior. Because regular stick-carrying hasn’t been reported in other wild chimpanzee communities, they proposed that that young Kanyawara chimpanzees may be learning the behavior from each other as a way of practicing for adult roles – a form of social tradition passed between juveniles previously described only in humans. Kahlenberg and Wrangham conclude by noting that:

Our findings suggest that a similar sex difference could have occurred in the human and pre-human lineage at least since our common ancestry with chimpanzees, well before direct socialization became an important influence.

So there you have it. One rhesus monkey study positing a biological and hormonal basis for gender-specific play, and another chimpanzee study emphasizing social learning… At least for now, the threads of nature and nurture impacting gender roles seem difficult to disentangle for non-humans, just as they are for us.

_____

![]() Hassett, J., Siebert, E., & Wallen, K. (2008). Sex differences in rhesus monkey toy preferences parallel those of children Hormones and Behavior, 54 (3), 359-364 DOI: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.03.008.

Hassett, J., Siebert, E., & Wallen, K. (2008). Sex differences in rhesus monkey toy preferences parallel those of children Hormones and Behavior, 54 (3), 359-364 DOI: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.03.008.

Berenbaum, S., & Hines, M. (1992). EARLY ANDROGENS ARE RELATED TO CHILDHOOD SEX-TYPED TOY PREFERENCES Psychological Science, 3 (3), 203-206 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1992.tb00028.x.

Kahlenberg, S., & Wrangham, R. (2010). Sex differences in chimpanzees’ use of sticks as play objects resemble those of children Current Biology, 20 (24) DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.024.